Archbishop John Quinn gave a very well-constructed speech at the National Federation of Priests’ Councils in Houston, Texas on April 13, 2010. I listed a few paragraphs to give you the flavor but it should be read in its entirety:

"I am here to pay tribute to you, the priests of the United States. You stand on the front line. You meet the angry or confused or troubled people at the Sunday Masses in your parishes and missions. You have to try to answer their questions about the worldwide crisis caused by priests and bishops around the world. You are the ones out there in the parishes whose hearts break at the anguish of our people over the robbed innocence of their children. And you weep inside over the desecration of something so beautiful, so cherished as the priesthood is to all of us. You are the ones who meet the children and the families, and try your best to walk with them in their search for peace and healing. You are there where the wound is.

I know that all over this country, in small towns and large cities, there are priests who stay up all night in a hospital waiting room with a distraught family whose teen-age daughter lies near death from an automobile accident. I know that there are priests in rural dioceses, like the priests I knew in Oklahoma, who drive hundreds of miles both ways to one or several mission churches on Saturday evenings and then have three Masses on Sundays with baptisms, counseling, youth groups and parish gatherings in the afternoon and evening…You are the priests who have persevered when your heart sank over an admired and gifted classmate who was removed from ministry because of allegations of abuse.

…We are at a critical point in the life of the church. Here and there commentators are beginning to compare it to the magnitude of the crisis of the Reformation. This is not the place to raise these cosmic issues. But I do believe it is the place to raise the question every priest must confront today. It is the question first raised by the Jesuit Karl Rahner: “Why would a modern man want to become or remain a priest today?”

…I think of my friend, Alfred Delp, who with his hands chained in a concentration camp, signed the paper of his final vows. I think of a brother priest who for long hours in the confessional listens to the pain and torment of [society's] unimportant people…I think of a brother priest who assists daily in a hospital at the bedside of death…I think of a brother priest who as a prison chaplain proclaims over and over the message of the Gospel with never any sign of gratitude. I think of the brother priest who (in a parish) with tremendous difficulty and without any clear evidence of success plods away at the task of awakening in just a few people a small spark of faith, of hope and of charity. These and many other forms and acts of renunciation, known to God alone, are still what is decisive in the priesthood.

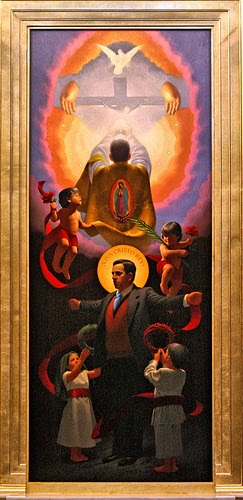

But there are men like these who have lived in and come from our own American dioceses.

Think of Emil Kapaun, a priest of Wichita, Kansas. In a prison camp in Korea he stole food from the commissary at night for his starving men knowing that he would be shot on sight if discovered. Depression and futility gripped many of the men in his unit. A Protestant chaplain with a wife and children at home was severely depressed and Emil knew he would die if something didn’t change. He deliberately said things to make him angry knowing that the experience of anger would bring him out of himself. It worked, and the man lived to return to his family. Emil tried everything to keep the men positive and hopeful. The men who got dysentery, he carried on his shoulders to the latrine and cleaned them. Eventually he got phlebitis and the guards took him off to die. The last thing his men heard was Emil assuring the guards he held no animosity or hatred for them.

Stanley Rother, whose bishop I was at one time, was a priest of Oklahoma City. He volunteered for the mission we had in Guatemala. He served the people with great dedication, teaching them their faith and instructing them in the social doctrine of the church. He carried on his ministry as priests he knew and worked with were murdered. His own catechists and parish leaders were abducted and murdered. Told that he was on the death list, he was urged to return to Oklahoma, which he did. But there only a short time, knowing clearly that it would mean certain death he decided to go back to Guatemala. He told his parents, “The Shepherd can’t run. I have to go back.” Father Rother was killed shortly after his return.

… Joseph Guetzloe, a Divine Word Father, was pastor of a Japanese community in San Francisco. When the Japanese were forced to move to segregation camps during World War II, Father Gutzloe asked to go with them. He voluntarily spent all the war years there with his people. A young priest, ordained one year, wrote to me about his experience during that first year and said, “ I have been looking for the lack of success in the lack of technique and finding it in the lack of holiness.”

…The cataclysmic avalanche of the sexual abuse scandal is a profoundly troubling experience for every priest. It touches not only the perpetrators and those so gravely hurt by them, but it is now engulfing the papacy itself and eroding the leadership and credibility of the bishops in the church. It forces us to ask the question of Karl Rahner, “Why would a modern man want to become or to remain a priest today?” How can an American priest persevere in the midst of such a shattering trial? How do we priests and how does the church persevere in time of severe trial?

…For St. Bernard, John the Baptist is the great image of the priesthood in the Gospel. He is the friend—the friend of the Bridegroom. An important role of the friend of the Bridegroom was that he was responsible for the joy of the guests at the wedding feast. This is how Christ presents himself in the Resurrection accounts: he is the minister of consolation. He consoles Mary at the tomb, He consoles the disciples locked in fear in the upper room, he consoles Thomas in his doubts. This is our role as priests—to console the Holy Church of God in a time of intolerable pain and suffering. We are called to be the ministers of consolation and of evangelical hope.

…And so, in a difficult time we should not forget that the great works of God have been accomplished in darkness. The people fled Egypt in the darkness; they crossed the Red Sea in the darkness; the Lord Jesus was born in Bethlehem in the darkness of night; He gave us the Eucharist and the priesthood in the darkness of the Last Supper; he died on the Cross when the Gospel says “darkness covered the earth.” He lay in the darkness of the tomb. On the third day, He rose again in the darkness, and the empty tomb was discovered “early in the morning while it was still dark.” God is at work even in the darkness.

What John of the Cross describes as the dark night of the soul has in our time become the dark night of the church. John explains that the dark night is a bewildering experience, it strips away all the visible supports. It brings a helpless, sinking feeling. But it is only truly the dark night when it is accepted as coming from God and borne in faith. The believer and the church who pass through the dark night in faith are led to the loss of everything secondary and to discover that God is not who they thought he was and they are not who they thought they were. It is the discovery that God is beyond everything we can articulate or conceive and it is the experience that we do not control God. The dark night is dark because God is infinite light overwhelming our limited capacities. It is in the experience of the dark night that the believer and the church come to know that God is all. This dark night of the church is a divine [method to teach] us painfully that we are incredibly poor and utterly dependent on God…"

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment